Paris has always been a city of romance, art, and rebellion-and for centuries, it was also home to one of the most openly visible, yet deeply misunderstood, professions in Europe: the escort. Not just any companion, but women and men who offered intimacy, conversation, and companionship in exchange for money, often navigating the edges of legality, social shame, and cultural fascination. Their story isn’t about crime or exploitation alone. It’s about survival, power, art, and the shifting tides of morality in one of the world’s most influential cities.

The Courtesans of the Ancien Régime

Long before modern dating apps or Instagram influencers, Paris’s elite relied on courtesans-women who were as much cultural figures as they were sexual partners. These weren’t streetwalkers. They were educated, often multilingual, and moved in the same circles as artists, philosophers, and nobles. Think of Madame de Pompadour, the official mistress of King Louis XV. She didn’t just sleep with the king; she shaped French art, politics, and fashion for over two decades. Her influence extended to the Louvre, Versailles, and even the rise of Rococo style.

By the 1700s, Paris had hundreds of these women, many of whom lived in luxurious apartments in the Faubourg Saint-Germain. They were paid in jewels, land, and pensions-not just cash. Some even owned businesses, ran salons, or published poetry. Their relationships with patrons were often formalized through contracts. In 1769, a courtesan named Madame du Barry signed a legal agreement that guaranteed her an annual income of 100,000 livres (equivalent to over $2 million today) for life. These women weren’t hidden. They were celebrated.

The Revolution and the Fall of the Courtesans

The French Revolution changed everything. When the monarchy fell in 1789, so did the system that supported courtesans. The new Republic didn’t just reject royalty-it rejected the entire idea of transactional intimacy tied to power. The National Assembly banned aristocratic privileges, including the right to receive state-funded mistresses. Many courtesans lost their homes, their patrons, and their status overnight.

Some disappeared into obscurity. Others became street prostitutes. By the 1820s, Paris had become a city of contrasts: glittering salons for the wealthy and grim alleyways where women sold themselves for bread. The government tried to control the chaos. In 1804, Napoleon introduced the réglementation system: all prostitutes had to register with the police, undergo weekly medical exams, and carry identification cards. It was the first state-sanctioned system of prostitution in Europe-and it made Paris the most regulated city of its kind.

The Belle Époque and the Rise of the Modern Escort

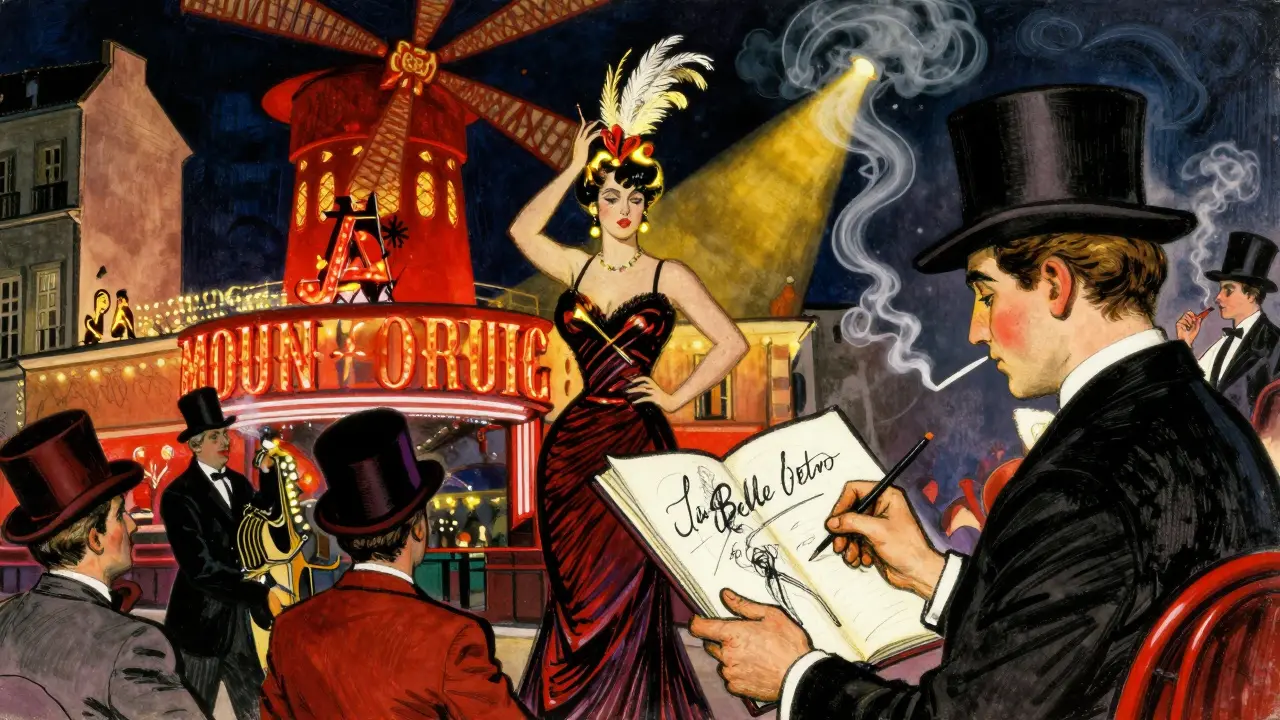

By the late 1800s, Paris had rebounded. The Belle Époque brought electric lights, cabarets, and the Moulin Rouge. This was the golden age of the modern escort-not the noble courtesan, but the glamorous, independent woman who chose her clients. Women like La Belle Otero and Liane de Pougy became celebrities. They appeared in newspapers, posed for painters like Toulouse-Lautrec, and were courted by princes and poets alike.

Unlike their predecessors, these women often lived alone, managed their own finances, and hired managers or chauffeurs. They didn’t need a patron. They had their own brand. Some even wrote memoirs. Liane de Pougy’s 1904 book Idylle Saphique became a bestseller, detailing her life as a lesbian escort who moved between aristocrats and artists. Her story wasn’t scandalous-it was aspirational.

Paris became known worldwide for its “demimonde”-the shadowy world of half-luxury, half-risk. Foreign visitors came specifically to experience it. Mark Twain wrote about it. Oscar Wilde was fascinated by it. The city didn’t hide its escorts; it advertised them.

From Legal to Illegal: The 20th Century Shift

The world wars changed the game. During World War I, military brothels were officially sanctioned near the front lines. But after 1918, public opinion turned. Feminist movements, religious groups, and reformers began calling prostitution a moral disease. In 1946, France passed the Loi Marthe Richard, which shut down all legal brothels. It was framed as a victory for women’s dignity. In reality, it pushed thousands of women into the shadows.

What followed wasn’t abolition-it was invisibility. Escorts didn’t vanish. They moved indoors. They began working through phone lines, private apartments, and later, classified ads. By the 1980s, escort agencies were operating under the guise of “companion services” or “modeling agencies.” The law didn’t ban paying for sex-it banned organizing it. So, agencies stopped owning buildings. They became referral networks. Clients paid the escort directly. No paperwork. No records. No trace.

Paris Today: The Digital Age and the New Companions

Today, Paris has an estimated 8,000 to 12,000 people working as escorts. Most are women, but men and non-binary individuals are increasingly visible. They don’t work on the streets. They work from apartments in the 7th, 16th, and 17th arrondissements. They use encrypted apps, discreet websites, and private social media profiles. Many are students, artists, or expats who see escorting as flexible work.

Unlike in the past, today’s escorts often set their own rates, choose their clients, and refuse services they’re uncomfortable with. Some specialize in language lessons, cultural tours, or emotional support. A 2023 survey by the Paris-based NGO Les Voix de la Rue found that 68% of escorts in the city said they chose this work because it offered autonomy-not because they had no other options.

Legal gray areas remain. While soliciting and brothel-keeping are illegal, paying for sex isn’t. That means clients aren’t prosecuted. But escorts are vulnerable to exploitation, harassment, and eviction. In 2021, the city launched a pilot program offering housing support and legal aid to sex workers who wanted to leave the industry. Only 12% applied. Most said they didn’t need help-they needed respect.

Why This History Matters

The story of escorts in Paris isn’t about sex. It’s about who gets to control a woman’s body, her time, and her value. From courtesans who shaped empires to modern workers who choose their own hours, the line between exploitation and empowerment has always been blurry. Paris didn’t invent escorting. But it did turn it into an art form.

Walk through the streets of Montmartre or the Latin Quarter today, and you’ll see plaques marking where courtesans once lived. You’ll see cafes where they drank wine with Degas. You’ll hear whispers of the women who turned their bodies into currency-and used that currency to buy freedom.

They weren’t just servants of desire. They were architects of culture. And their legacy? It still walks the streets of Paris.

Were escorts in Paris always illegal?

No. From the 1700s until 1946, prostitution was legal and regulated in Paris. The government required registration, medical exams, and identification for sex workers. Brothels were licensed and inspected. The 1946 law, named after activist Marthe Richard, shut down all brothels and criminalized organized prostitution, but not the act of paying for sex itself.

How did courtesans differ from street prostitutes?

Courtesans were elite companions who often had formal education, lived in luxury, and built long-term relationships with wealthy patrons. They were part of high society, attended salons, and sometimes influenced politics or art. Street prostitutes, by contrast, worked in public spaces, had little financial security, and were socially marginalized. The two groups rarely interacted and occupied entirely different social classes.

Did any famous artists or writers have relationships with escorts?

Yes. Toulouse-Lautrec painted dozens of courtesans and frequented their salons. Oscar Wilde was known to visit Parisian escorts during his travels. Marcel Proust referenced them in his novels, and Jean Cocteau had long-term relationships with male escorts. Many artists saw them not as victims, but as muses, collaborators, and symbols of modern freedom.

What’s the legal status of escorts in Paris today?

Paying for sex is not illegal in France. However, organizing, advertising, or managing sex work is. Escorts can work independently, but they can’t hire staff, rent fixed locations for business, or use public platforms to advertise. This creates a legal gray zone: clients are safe, but workers are vulnerable to exploitation and police raids.

Are there any museums or landmarks in Paris related to escort history?

There’s no official museum, but several sites mark this history. The Musée d’Orsay has paintings of courtesans by Lautrec and Renoir. The plaque at 12 Rue de la Fontaine in the 16th arrondissement marks the former home of Liane de Pougy. The Musée de la Magie in the Marais displays old advertising cards from 19th-century escort agencies. Even the Palais Garnier has a hidden corridor once used by courtesans to enter private boxes.